Researchers from our vaccine design team recently participated in a Reddit ‘Ask Me Anything’ about our SARS-CoV-2 vaccine research. Reddit users asked over a hundred questions by the time the live event ended — we are sorry we could not address them all.

We were lucky to be joined by Lexi Walls, a postdoctoral scholar in the UW Veesler lab, who recently helped lead an effort to determine the structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein by cyro-electron microscopy. “It was so wonderful to see such a broad audience pour in so many well-thought out questions about our research,” said Erin Yang, a Baker lab graduate student who helped organize the event.

Here is our pick for the top five vaccine-related questions from our Reddit AMA:

If a vaccine was created, and proven to work, how long would it take for it to be mass produced and for it to reach the general public?

The projections of 1 year to 18 months to have an FDA approved vaccine are probably accurate — if some of the vaccine candidates that [are] either in development or about to start clinical trials as of today do in fact provide protection (which we don’t know yet) and everything goes well.

The projections of 1 year to 18 months to have an FDA approved vaccine are probably accurate — if some of the vaccine candidates that [are] either in development or about to start clinical trials as of today do in fact provide protection (which we don’t know yet) and everything goes well.

Vaccines, like all medicines, have to be very safe. The safety bar for vaccines is very high as they are administered to large numbers of people. Much of the time that will be required to get a vaccine out will be devoted to ensuring that vaccine candidates are very safe, as well as effective.

— Lauren Carter

Is there a chance we’ll ever develop one day the technology to create and manufacture vaccines for new diseases, quickly enough to tackle their extremely damaging first wave (so essentially have a vaccine ready within 2, 3 months of a disease being discovered)?

Potentially. There will always be a need for safety trials, but new vaccine platforms that are modular (like ours) — once they have been proven in clinical trials — could be developed quickly for new indications. As an example, annual flu vaccines are manufactured relatively rapidly, but there is room for further improvement. — Lauren Carter

One long-term goal (which will not be ready for this pandemic) would be to create vaccines that could provide universal coverage against any family of viruses that has a high chance of causing a pandemic. For example, one could imagine having a single vaccine that protects against all possible coronaviruses, another vaccine that protects all possible flu viruses, etc. Based on what we know about how the immune system responds to flu, a universal flu vaccine does look possible as there are pieces of flu that are conserved between all flu viruses that infect humans. Coronaviruses are less studied in this regard. Hopefully greater study of them in the coming years will show that such a vaccine could be possible.

One long-term goal (which will not be ready for this pandemic) would be to create vaccines that could provide universal coverage against any family of viruses that has a high chance of causing a pandemic. For example, one could imagine having a single vaccine that protects against all possible coronaviruses, another vaccine that protects all possible flu viruses, etc. Based on what we know about how the immune system responds to flu, a universal flu vaccine does look possible as there are pieces of flu that are conserved between all flu viruses that infect humans. Coronaviruses are less studied in this regard. Hopefully greater study of them in the coming years will show that such a vaccine could be possible.

— Dan Ellis

What are we seeing in the human antibodies from recovered patients and how does that influence a potential vaccine? Are there other proteins we can target aside from the spike protein?

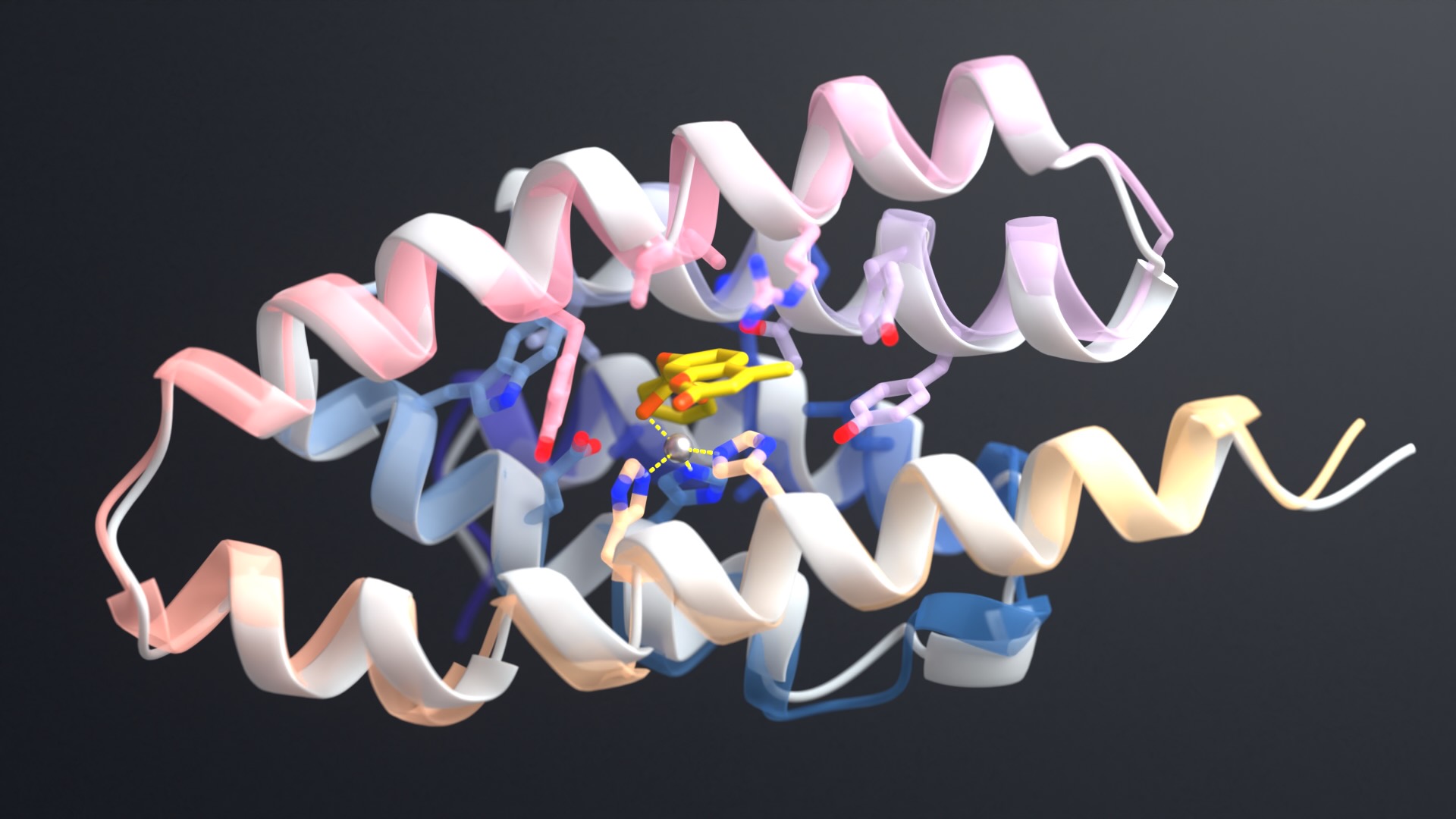

There are a variety of proteins present in coronaviruses, but the spike protein is the major vaccine and antibody target because it is present on the outside of virus and is the major protein that our immune systems target during natural infection. The spike protein is also the workhorse of viral entry — the spike protein’s role is to bind to host cells and fuse viral and host membranes to allow for infection. The spike is therefore the first target the immune system sees and acts against. This also means that if we can target antibodies to it, we could prevent viral entry into host cells completely and block infection (which is the ultimate goal!). The most promising target on the spike protein is called the receptor binding domain, the goal being to block the interaction with host (our) receptor. If this interaction is blocked, then the virus cannot enter cells and no infection can occur.

There are a variety of proteins present in coronaviruses, but the spike protein is the major vaccine and antibody target because it is present on the outside of virus and is the major protein that our immune systems target during natural infection. The spike protein is also the workhorse of viral entry — the spike protein’s role is to bind to host cells and fuse viral and host membranes to allow for infection. The spike is therefore the first target the immune system sees and acts against. This also means that if we can target antibodies to it, we could prevent viral entry into host cells completely and block infection (which is the ultimate goal!). The most promising target on the spike protein is called the receptor binding domain, the goal being to block the interaction with host (our) receptor. If this interaction is blocked, then the virus cannot enter cells and no infection can occur.

As for what we are seeing from human antibodies from infected patients… this is a pre-print (not yet peer-reviewed- a way to publicly post results early to allow for sharing of knowledge as fast as possible, but submitted to a scientific journal to go through that process) on just that topic!

— Lexi Walls

What makes creating a vaccine so hard? I genuinely want to understand the work and tech that goes behind creating something that kills a virus.

This is a really complex question, and we’ll only be able to provide a partial answer. If you are curious about how vaccines and drugs are developed, here are a few other resources: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/vaccine-development

This is a really complex question, and we’ll only be able to provide a partial answer. If you are curious about how vaccines and drugs are developed, here are a few other resources: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/vaccine-development

At a very basic level, making vaccines is hard because we don’t fully understand how the immune system perceives pathogens and most effectively marshals its forces (T cells, B cells, etc.) to eliminate pathogens. We know some things, like antibodies and T cells are important. So the job of vaccinologists is to make a thing that stimulates the immune system — which we do not fully understand — in just the right way. You want to raise the right flags for the immune system to see in order to identify the threat, but you don’t want to overwhelm the system or alert it to the wrong thing.

Another challenge in making vaccines is that they must be exceedingly safe. Vaccines are administered to large numbers of healthy people, so they must do no harm. Making a thing that provokes a potent, protective immune response but that is totally safe requires a lot of knowledge, skill, and operational excellence.

Finally, viruses and bacteria are experts at evading the immune system — they have developed lots of tricks to subvert or suppress immune responses. So you have to know enough about the bug (the virus or bacterium or whatever) to teach the immune system how to eliminate it, despite the tricks the bug tries to play.

— Neil King

How many vaccine candidates are there currently? Where are the trials being conducted?

A few different vaccine candidates from other groups have entered the earliest stage of clinical testing, and many others are racing to get there. A handful of patients have been injected in Seattle as part of one mRNA vaccine trial (Phase 1).

A few different vaccine candidates from other groups have entered the earliest stage of clinical testing, and many others are racing to get there. A handful of patients have been injected in Seattle as part of one mRNA vaccine trial (Phase 1).

This is an incredible moment for science — all hands are on deck, moving quickly but safely.

— Erin Yang