IPD researchers together with collaborators at the National Institutes of Health have developed experimental flu shots that protect animals from a wide variety of seasonal and pandemic influenza strains. The lead vaccine candidate has entered human clinical testing at the NIH. If it proves safe and effective, these next-generation influenza vaccines may replace current seasonal options by providing protection against many more strains that current vaccines do not adequately cover.

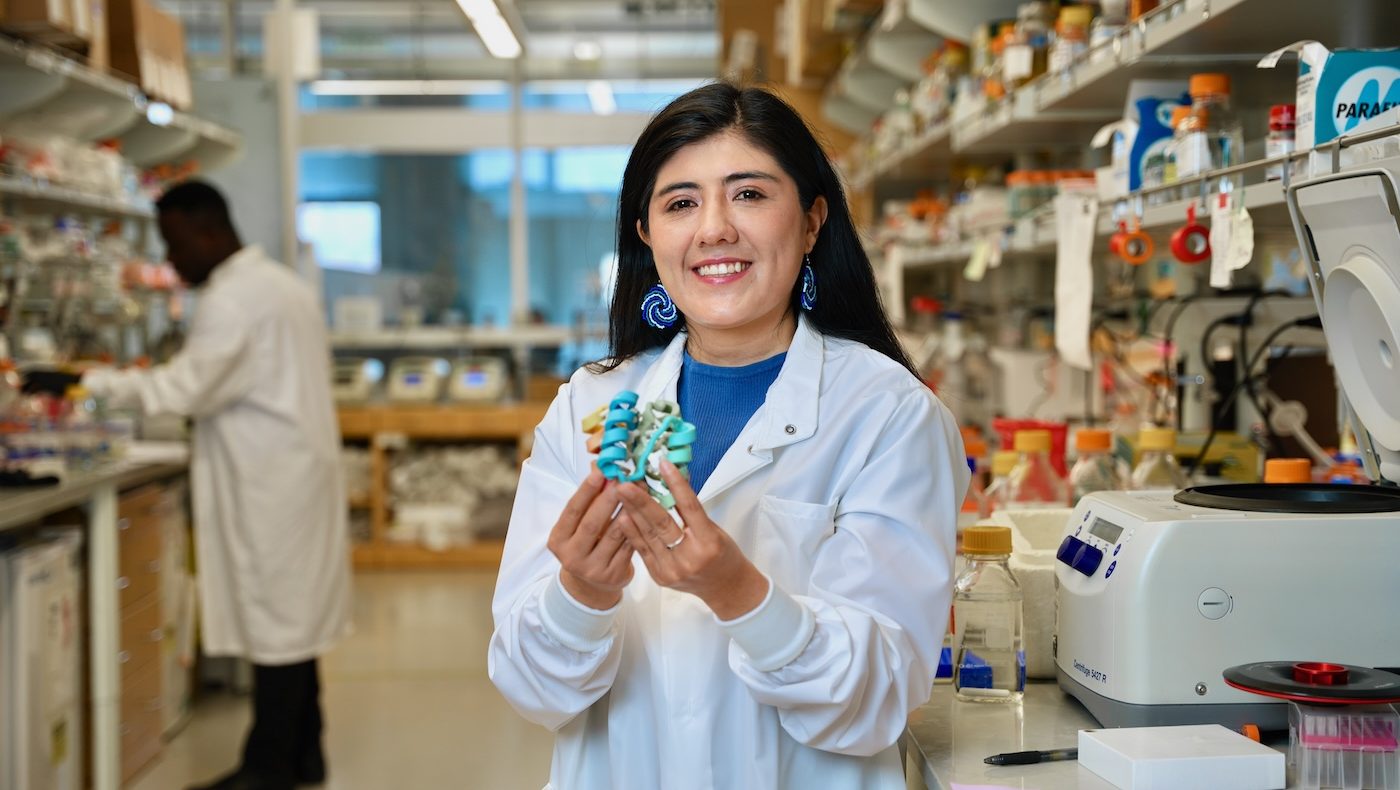

A study detailing how the new flu vaccines were designed and how they protect mice, ferrets, and nonhuman primates appears in the March 24 edition of Nature. This work was led by researchers at the Institute for Protein Design and the Vaccine Research Center, which is part of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the NIH.

Influenza virus causes an estimated 290,000–650,000 deaths per year. Available flu vaccines, which need to be taken seasonally, often fail to protect against many circulating flu strains that cause illness, and the threat of another influenza pandemic looms.

“Most flu shots available today are quadrivalent, meaning they are made from four different flu strains. Each year, the World Health Organization makes a bet on which four strains will be most prevalent, but those predictions can be more or less accurate. This is why we often end up with ‘mismatched’ flu shots that are still helpful but only partially effective,” said lead author Daniel Ellis, a research scientist in the laboratory of Neil King at the IPD.

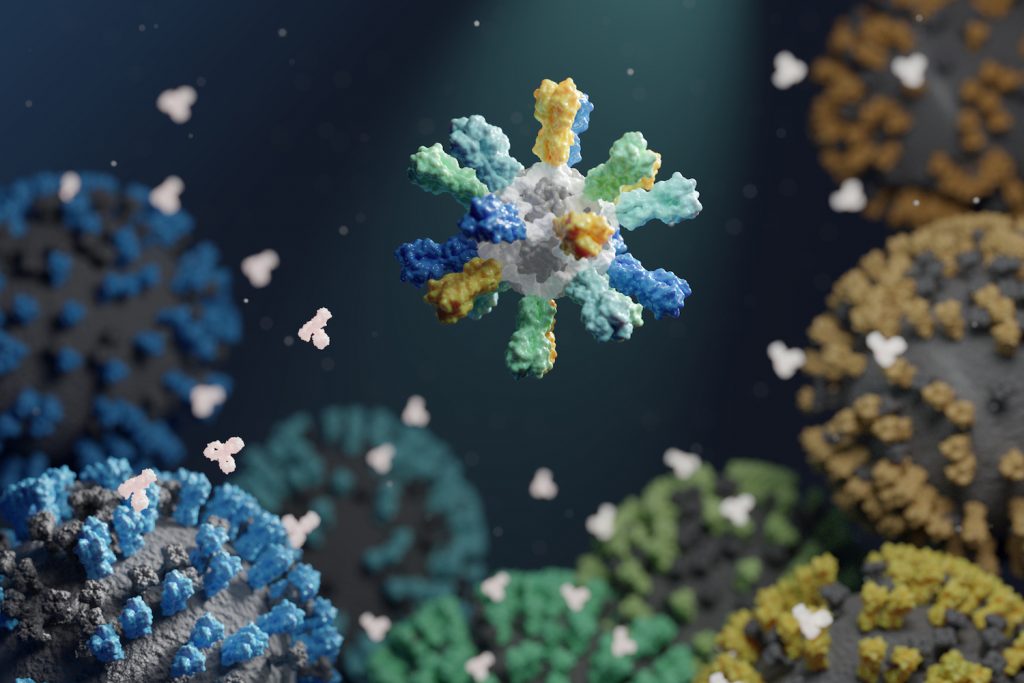

To create improved influenza vaccines, the team attached hemagglutinin proteins from four different influenza viruses to custom-made protein nanoparticles. This approach enabled an unprecedented level of control over the molecular configuration of the resulting vaccine and yielded an improved immune response compared to conventional flu shots. The new nanoparticle vaccines, which contain the same four hemagglutinin proteins of commercially available quadrivalent influenza vaccines, elicited neutralizing antibody responses to vaccine-matched strains that were equivalent or superior to the commercial vaccines in mice, ferrets, and nonhuman primates. The nanoparticle vaccines—but not the commercial vaccines —also induced protective antibody responses to viruses not contained in the vaccine formulation. These include avian influenza viruses H5N1 and H7N9, which are considered pandemic threats.

“The responses that our vaccine gives against strain-matched viruses are really strong, and the additional coverage we saw against mismatched strains could lower the risk of a bad flu season,” said Ellis.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM120553, HHSN272201700059C as well as intramural funding to the Vaccine Research Center), Open Philanthropy Project, Audacious Project, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, University of Washington Arnold and Mabel Beckman cryo-EM center, and a Pew Biomedical Scholars Award.